Earlier today, I had the pleasure of speaking at the Margins to Centre Conference 2025 at the University of York. The conference seeks to amplify the voices of marginalised communities and this year the conference explored the theme of Belonging. Here’s the text of my keynote:

=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.=.

In The Tale of Despereaux, Kate DiCamillo writes

“Stories are light. Light is precious in a world so dark. Begin at the beginning. Make some light.”

In a world so often overwhelmed by fear, confusion, and division, storytelling becomes a sacred act. It is through stories that we remember who we are, where we come from, and what we are called to become. Stories don’t just entertain—they heal, they guide, they connect. They pass down truth wrapped in empathy.

When we tell stories—especially those of the marginalised, the unheard, the silenced—we are not just sharing information, we are shining light. And in spiritual traditions across the world, light is a symbol of hope, wisdom, and divine presence.

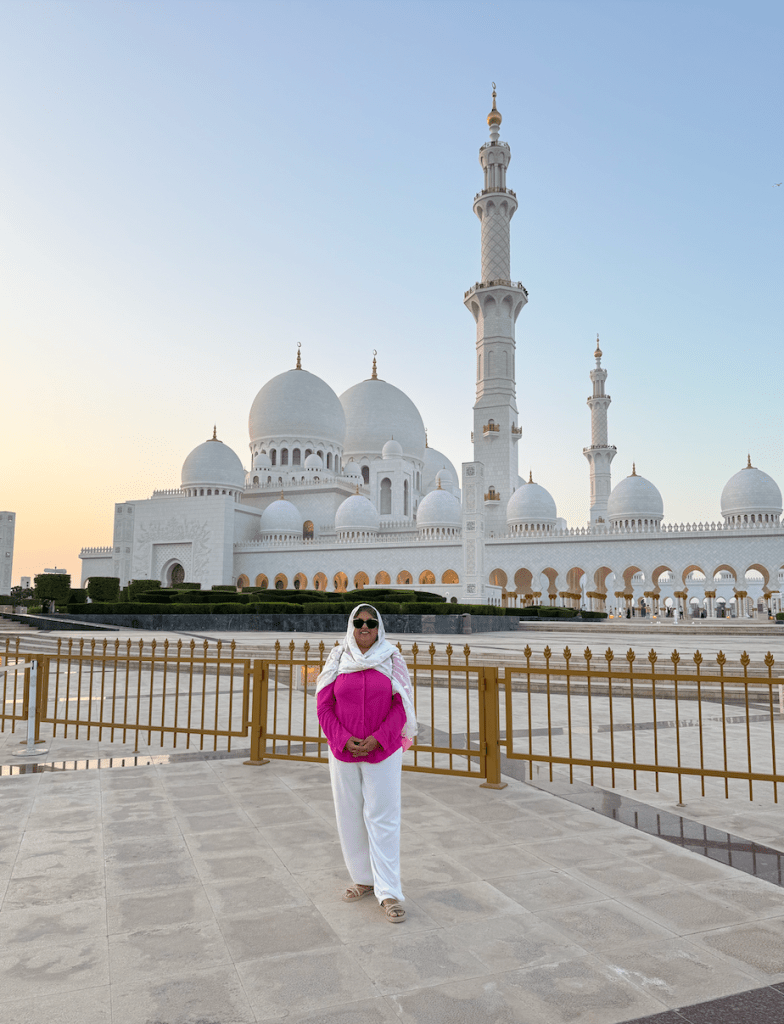

In Christianity, light is the symbol of Christ—the light that shines in the darkness. In Judaism, the lighting of the Menorah marks the miracle of resilience and faith. In Hinduism, the festival of Diwali celebrates the triumph of light over darkness, good over evil. In Buddhism, enlightenment itself is awakening into the light of truth. And In Islam, my own faith tradition, God is described as the Light of the heavens and the earth.

“God is the Light of the heavens and the earth. His light is like a niche in which there is a lamp, the lamp is in a crystal, the crystal is like a shining star, lit from ˹the oil of˺ a blessed olive tree, ˹located˺ neither to the east nor the west, whose oil would almost glow, even without being touched by fire. Light upon light!” (Quran Surah An-Nur, verses 35-37)

To tell a story, then, is to make light in a darkened world. It is to participate in something deeply spiritual—to spark connection, compassion, and courage. Personal stories shine a little light—and explain the meaning of belonging far better than I ever could in theory alone.

And that’s why I’d like to start with a story.

So this is a very recent story – something that happened a few weeks ago on Eid.

My children were all over and I’d managed to sneak upstairs to get dressed whilst they laid the table for dinner. I could hear lots of chatting and laughing but couldn’t make out any of the conversations taking place. As a mother whose children are now adults and have flown the roost, there is nothing quite so heartwarming as hearing your children laughing (and occasionally arguing) together as they used to do when they were younger. On this occasion, the conversation revolved around my ‘status’ whether I was British born or in their words “an immigrant”.

Now this is a word I’ve had hurled at me on many an occasion – personally, through the television, and more recently via social media. Those of us of a certain age will remember several British TV programmes that portrayed immigrants—particularly those from South Asian, Caribbean, and African backgrounds—through stereotypical or negative lenses. These portrayals often reflected the racial tensions and political climate of the time. Programmes that include Love Thy Neighbour, Mind Your Language, Til Death Us Do Part and It Ain’t Half Hot Mum, to name but a few. At the time, these shows were often hugely popular and considered “mainstream comedy.” However, they played a major role in reinforcing negative public attitudes toward immigrants and minorities, with more sinister connotations than that being implied by my children. If I was an immigrant, my children were 1st generation immigrants not as they had thought 2nd generation immigrants.

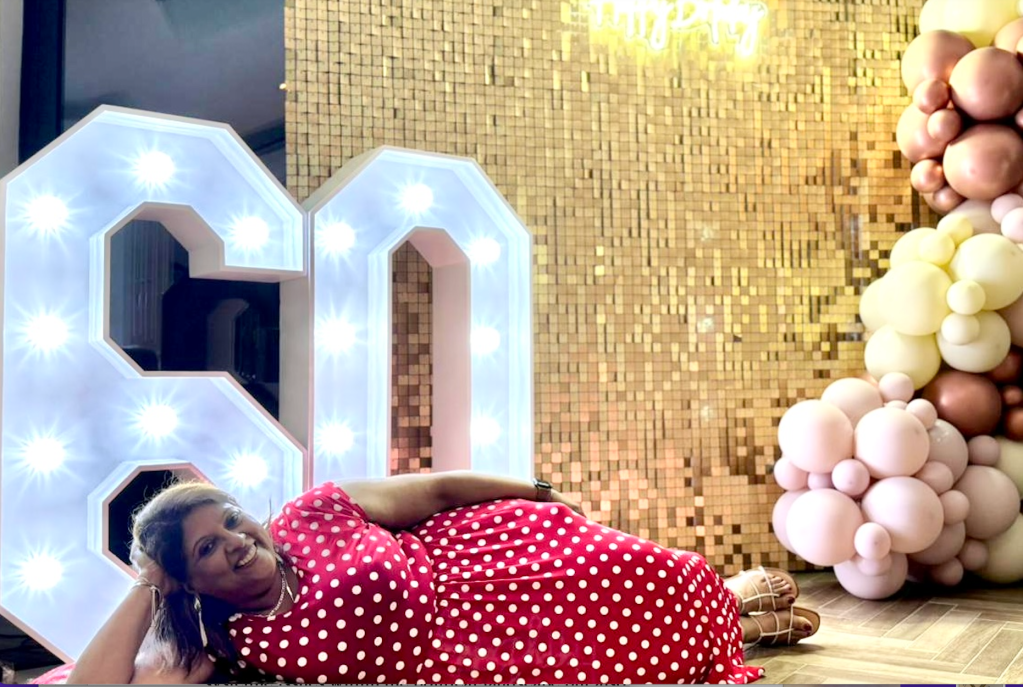

So here I am, a British Muslim, a child of immigrants, an immigrant myself, who also happens to be a member of a nation that has been my home for over sixty years. My story isn’t unique; it’s the story of countless others who’ve made this country their own, striving to belong while navigating the complexities of inclusion, identity, and representation.

Belonging is a deeply human need. It’s the comfort of knowing you’re seen, valued, and accepted not tolerated. But for many, especially those of us from diverse backgrounds, belonging has often felt like something that we have to earn, as opposed to something that is inherently ours. My parents arrived here in 1965 with 6 children – the eldest 18 years old and the youngest just 11 months (I was the 11 month old). They will have come with fear, apprehension, trepidation but also with aspirations for their children, optimism for the endless possibilities that lay ahead – and as devote Muslims an unwavering trust in God. They worked tirelessly to build a life, contributing to a country that promised opportunity and fairness. Yet, as their child in the 60’s, 70’s and 80’s, I was raised in a world where my claim to Britain as home was constantly questioned — a world it seems we’ve sleepwalked right back into.

Identity is at the core of belonging. I’m British, Muslim, South Asian, a woman, a daughter, a wife, mother, mother-in-law and grandmother. But for too long, people “like me” have been asked to choose – am I British or Muslim, British or Pakistani, British or ‘other.’ Why do I, should I, have to choose? True belonging means being accepted for all of who I am, without having to hide any part of myself. It means understanding that being British isn’t just one story, but lots of different ones woven together.

Inclusion goes beyond tolerance. It’s about making space at the table, not just as guests but as equal members of society. It means seeing our stories reflected in classrooms, boardrooms, and in the media. It means hearing our voices in Parliament—not just as tokens to satisfy diversity quotas or to ensure legal compliance in candidate shortlists, but as genuine representatives with the power to influence and lead. Too often, minorities are used as fodder to tick a box, to ensure rules are not broken regarding the election of candidates, rather than being valued for their contributions and perspectives. Representation is not just about numbers; it is about influence, agency, and the power to shape the future. When young British Muslims see themselves reflected in positions of power, they don’t just aspire — they believe. They don’t want to be merely tolerated — a word that suggests people are simply putting up with them — but actively included, with their rights, dignity, and security fully upheld in society.

In 2011, Baroness Sayeeda Warsi, then co-chair of the Conservative Party, stated that Islamophobia (a term I personally dislike so prefer to use the term anti-Muslim hatred) had “passed the dinner-table test.” By this, she meant that expressing anti-Muslim sentiments had become socially acceptable in polite society, even among middle-class individuals during casual conversations. She observed that while overt racism and homophobia were largely condemned, anti-Muslim remarks were often tolerated or overlooked. Over a decade later, in her 2023 keynote speech titled “Muslims Don’t Matter,” Baroness Warsi reiterated her concerns, emphasising that Muslims are still often excluded from decision-making processes and are held to higher standards than other citizens. She called for a collective effort to address and dismantle systemic anti Muslim hatred in British society.

The road to belonging is paved with countless challenges. We live in times where division feels stronger than unity, where difference is sometimes feared rather than embraced. Anti-Muslim hatred, racism, and prejudice still cast shadows over our collective progress.

Those of us who grew up without smart phones will know what I’m referring to when I mention the ‘Norman Tebbit cricket test’. In 1990, Norman Tebbit, a Conservative politician, suggested that you could measure the loyalty and integration of immigrants in the UK by asking which national cricket team they support—especially when England played against the country of their or their parents’ origin (e.g., India, Pakistan, the West Indies). Tebbit argued that if British-born people of immigrant backgrounds supported their parents’ home countries over England in sports, it showed a lack of allegiance to Britain and a failure to integrate. This was highly controversial at the time, as critics saw it as oversimplifying identity and ignoring the multicultural reality of modern Britain. It was seen as what today we would call dog whistle politics – a shout out to nationalism, implying that immigrants must erase their cultural heritage in order to be truly British. Many public figures, especially from ethnic minority communities, criticised the idea at the time, pointing out that cultural pride and national loyalty are not mutually exclusive—you can be proud of your heritage and still be loyal to the country you live in.

Now this was 35 years ago – but has much changed? Belonging should not be about proving our allegiance through something as trivial as sport, or whether we know the name of our local pub. It’s about our contributions, our values, and our commitment to the shared future of this nation.

Moreover, we cannot ignore the increasing abuse and hatred directed at Muslim communities by the extreme right wing over the last 20 years. Groups like the English Defence League (EDL), Britain First, Patriotic Alternative, and many other far-right groups who have sought to spread fear, division, and misinformation about Islam and Muslims. Their rhetoric fuels hostility, leading to real-life consequences – verbal and physical attacks, the vandalism of mosques, and the marginalisation of entire communities. This rise in violent right-wing extremism is not just a threat to Muslims; it is a threat to the very fabric of our society.

The power of this hatred was tragically demonstrated in the riots that erupted across the country following the attack in Southport – an attack committed by a man who was not a Muslim. Yet, despite this fact, far-right groups seized the opportunity to inflame tensions, using misinformation and fear to incite violence and target innocent Muslim communities. This reaction revealed how prejudice, rather than facts, continues to shape the narratives pushed by extremists. Such events should serve as a wake-up call for all of us: we must not allow hatred to dictate our national discourse, nor permit extremists to exploit tragedy for their own agendas. True belonging is about being seen and accepted for everything we are, without needing to shrink or hide parts of ourselves. It’s about recognising that British identity isn’t a single story, but a rich mix of many voices and experiences.

We need to recognise and celebrate the remarkable contributions of British Muslims in our society.

Such as Sir Mo Farah, who came to Britain on a boat, a refugee, now a four-time Olympic gold medallist who has inspired a generation with his resilience and determination.

Nadiya Hussain, who not only won the hearts of the nation as the Great British Bake Off champion but continues to use her platform to champion inclusivity and representation. Not to mention the fact that she also made the late Queens Elizabeth II’s 90th birthday cake!

Sadiq Khan, the first Muslim Mayor of London, whose leadership has demonstrated that British Muslims belong at the highest levels of public service.

Mo Salah – a powerful symbol, not just as an elite footballer but as a global Muslim icon—someone who has helped shift perceptions through both his excellence on the pitch and his character off it. Salah is unapologetically and proudly Muslim—he prostrates after scoring, thanks God in interviews, and shares Ramadan fasting and Eid publicly. As someone who knows so little about anything football related, even I will never forget the chant that reverberated through the stadium in 2018:

“Mohamed Salah, a gift from Allah

He came from Roma to Liverpool

He’s always scoring, it’s almost boring

So please don’t take Mohamed away”

His popularity among fans reflects how his presence and performance have contributed to fostering a more accepting and diverse environment within football culture.

Mishal Husain’s appointment as a prime-time BBC news presenter marked a historic moment — the first time a visibly Muslim woman held such a prominent role in British broadcast journalism. Her presence signalled that Muslim identity and mainstream British identity were not mutually exclusive. As the first high-profile Muslim woman in a prime-time role at the BBC, Mishal Husain shattered a glass ceiling for many who had never seen someone like themselves on screen in such a position of authority and trust. She became a symbol of what is possible for British Muslims, particularly women, in public life. In a media landscape that often frames Muslims through the lens of conflict, terrorism, extremism, or cultural difference, Mishal Husain stood out by simply doing her job with clarity, professionalism, and integrity. In doing so, she helped challenge narrow stereotypes and offered a new narrative of normality, competence, and credibility.

Humza Yousaf made history as the first Muslim and first person of South Asian descent to become First Minister of Scotland. His ascent to one of the highest political offices in the UK sends a powerful message: that young Muslim men can — and should — see themselves at the heart of national leadership. Humza Yousaf does not hide his Muslim identity; instead, he wears it with dignity while championing an inclusive, progressive vision of politics. He shows that you can be both unapologetically Muslim and deeply committed to public service, social justice, and civic leadership. He isn’t just a symbol — he’s a leader. For young Muslim men growing up hearing that they don’t belong, Hamza’s presence in power affirms that they do. His story disrupts the narrative that Muslims are always outsiders in British public life.

These individuals are just a drop in a very big ocean. How can we talk about the countless and often unrecognised doctors saving lives in the NHS frontline, artists, entrepreneurs, and activists shaping the cultural and social fabric of Britain. Muslims are an integral part of this country’s success.

I’m going to finish with another story – something that happened nearly 35 years when I moved to Wales and joined a new GP practice. When I walked into the surgery, the doctor (a man) didn’t look up just indicated to the chair next to his desk. He was looking at some notes on his desk. After an awkward silence, without looking up he says “so how the heck do I pronounce that then”. Not one to cower I responded “it can’t be that difficult – it’s only five letters – try it”. After another silence he says “hmm – Hifsa. So where the heck are you from then?”. To which I responded “Leeds – where are you from?”. His response was “no you know what I mean – where are you ACTUALLY from”. Again I replied “I’m from Leeds”. He then said – “no I mean where are your parents from” to which I again replied “they’re from Leeds too”. It was only at this point he actually looked up from his desk, realising he wasn’t going to get the answer he was for and decided to ask me how he could help me.

Belonging isn’t a gift granted by others – it’s a right that we claim. We don’t need to shrink ourself to fit into society’s narrow definitions. Our identity is not a contradiction; it is a bridge. Belonging isn’t just about fitting in; it’s about shaping the space we inhabit. We belong because we’re here. We belong because we contribute, we create, we build, and we serve. And by doing so, we ensure that Britain is a place where everyone, regardless of race, religion, or heritage, doesn’t just live—but truly belongs.